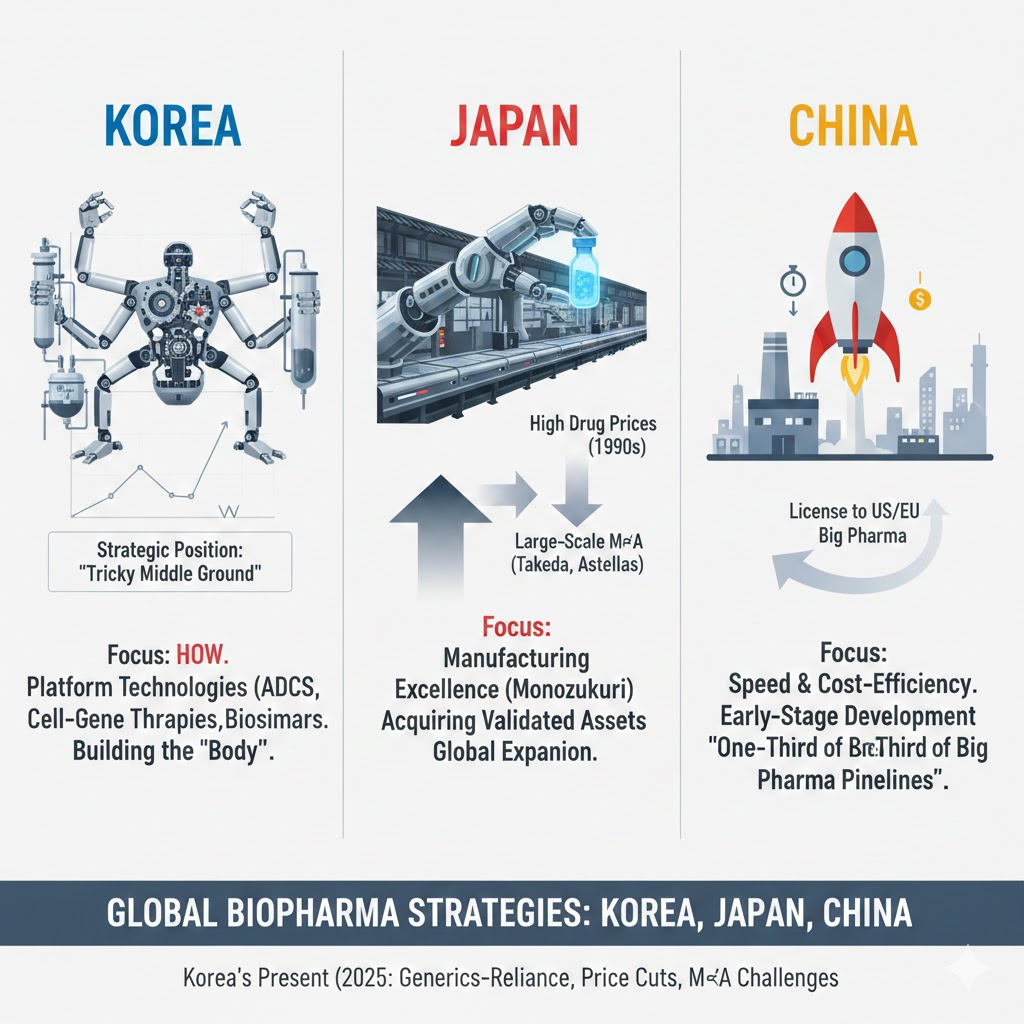

When you look at the Korean biopharmaceutical landscape, a unique pattern emerges. Many companies that have achieved a degree of success—like Alteogen, Samsung Biologics, and Celltrion—tend to focus less on why a pipeline is being developed and more on how it’s being built. Rather than concentrating on specific disease areas or therapeutic targets, they emphasize technology—often tied to modality-driven platforms like ADCs, cell and gene therapies, bispecific antibodies, and others.

The strategic thinking around why a particular target should be pursued, or how competitive a product might be a decade from now, is often left to the originators. Korean companies, in contrast, seem to specialize in building out the “body”—the executional arms and legs—rather than the “head,” which represents deep market foresight, scientific vision, and disease area leadership.

What About Japanese Pharma?

Japan also places a strong emphasis on manufacturing excellence—what’s often referred to as monozukuri (ものづくり). Like Korea, Japanese companies don’t typically lead with a compelling rationale for why a specific target is worth pursuing. Instead, they tend to acquire assets that have already cleared a minimum threshold of clinical validation.

And Then There’s China

China, meanwhile, has become a powerhouse in speed and cost-efficiency. It’s now common practice for Chinese companies to complete early-stage nonclinical and clinical development at a fraction of the cost and time, then license those assets out to big pharma in the U.S. or Europe. In fact, some statistics suggest that nearly one-third of big pharma pipelines now originate in China—and that proportion is only expected to grow.

Korea’s Strategic Position

Korea finds itself in a tricky middle ground. It can’t match China in speed or cost, nor does it have a mature domestic market with strong capital reserves. Given these constraints, it makes sense that many Korean companies focus on platform technologies or start with biosimilars—products with validated targets and lower risk profiles.

In this context, it’s arguably the smartest strategy available.

Japan’s Past, Korea’s Present

Back in the early 1990s, Japan’s pharmaceutical market benefited from high drug prices, which fueled growth. But as the government began cutting prices on new drugs, Japanese pharma responded with large-scale mergers and acquisitions—Takeda, Astellas, and Daiichi Sankyo being prime examples. These companies then pivoted toward global expansion rather than doubling down on domestic pipelines.

Korea’s situation in 2025 is different. Unlike Japan in the ’90s, Korea’s pharma industry has few new drugs and relies heavily on generics for revenue. With recent government-driven price cuts, many companies are bracing for a significant hit to their bottom line.

However, unlike Japan, large-scale M&A seems unlikely in Korea. Many Korean pharmaceutical companies are family-owned or run by founding families, and there’s a strong preference for direct management. This makes equity-diluting mergers—common in Japan’s past—much harder to execute in Korea, especially with major shareholders reluctant to give up control.